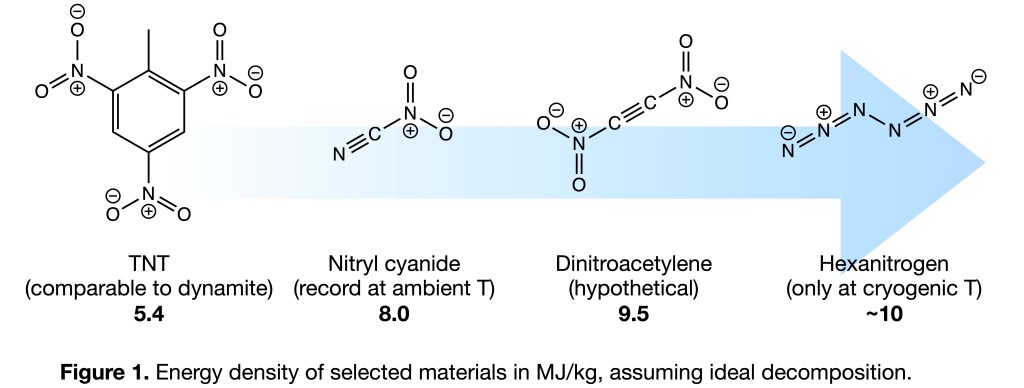

In a recent article, Lara Harter and Guillaume Belanger-Chabot (both at Université Laval in Quebec) and I computationally investigate the feasibility of making dinitroacetylene (C2(NO2)2; see Fig 1). If synthesized, this compound would be the most energy dense chemical ever made that remains persistent at ambient conditions. It would release about 9.5 MJ of heat for every kilogram combusted into CO2 and N2. That is a lot. It is possible that the only way to cram more chemical energy into a material is to make a nitrogen allotrope, such as the still hypothetical N4.

Indeed, you might have read about the recent, impressive synthesis published in Science by Qian et al. of N6 — two azide groups stitched together to form a linear chain of nitrogen. That compound is, at least to the best of my knowledge, more energetic than anything (non nuclear) in existence. However, N6 is also stupendously prone to decomposition into N2 and can only persist at cryogenic temperatures.

Our recent theory paper on dinitroacetylene is a good example of Swedish–Canadian partnership in research, and highlight a fascinating target for molecular engineering and design. But in this day and age, its publication also made me reflect on the reasons for pursuing such materials in the first place. How does one get tangled up into the pursuit of the world’s most energetic compounds?

When I began my scientific career as a PhD student in 2006, it was a different time, to say the least. War and conflict felt largely delegated to history. As an avid space nerd, I took on a challenging project aimed at developing a more environmentally friendly rocket propellant based on ammonium dinitramide, NH4N(NO2)2. The goal was to help replace the toxic perchlorates still used in heavy space launchers. It was rocket science, and the perfect project for someone eager to work hard and learn a lot, but couldn’t quite decide between pursuing theory or experiments, academia or industry. I soon found myself working simultaneously in quantum, polymer, inorganic, and analytical chemistry.

This rather unique PhD experience was, ironically, made possible by the project being severely underfunded. The research was designed for, and clearly required, two PhD students to succeed: one focused on theory and another on experiments. But only one was funded! This situation turned out well for me, as I ended up doing the work of two and learning more than I could have imagined. Not because anyone pressured me, but because I found the research stimulating, loved learning, and worked in an environment that was supportive and above all trusting. I wish that more young researchers could benefit from growing by experiencing such freedom under responsibility. But that is another topic altogether.

My PhD thesis Green Propellants covers not only theory and experiments on ammonium dinitramide and polymers, but predictions of several unknown materials. The crowning achievement was arguably the successful nitration of dinitramide, making N(NO2)3, the world’s largest nitrogen oxide. My PhD advisor Tore Brinck and I jokingly called N(NO2)3 a ”propeller propellant” due to its C3 symmetry. While a very potent oxidizer, this molecule (like N6) decomposes above -20C and is of no real use besides academic curiosity.

Later, during my first postdoc with the (I dare say legendary) Karl Christe at the University of Southern California, Guillaume and I managed to make something considerably scarier: nitryl cyanide, NCNO2. This compound currently holds the record for energy density of compounds persistent at ambient conditions, sporting 8 MJ/kg. It took about three years to synthesize and characterize. I bring that up to make a point: the reason we were able to persist for so long was that I had convinced myself (and Guillaume) using careful quantum chemical calculations that NCNO2 really could be made. Theory also gave us the vibrational spectroscopy bands to look for, and which nuclear magnetic resonance signals that would confirm its presence.

Many others must have tried to make NCNO2 before us, the structure is so simple. But without knowing that a pursuit is possible, there is less reason to persist. Persistence is often needed to advance science, and ours was well motivated!

So why did I decide to pursue trinitroamine and nitryl cyanide, compounds that most chemist would tell you cannot be made? Mostly, I wished to learn about the limits of chemical bonding – how much energy one could squeeze into electronic configurations of matter before reality objected. My motivation was curiosity.

While energetic materials are fascinating for pushing the boundary of chemical possibility, they are also useful in everything from road construction to beautiful (if often environmentally questionable) fireworks to lifesaving air bags, and space flight. However, their usage these days is increasingly military. The ethics of the latter is more complex than most admit. Personally, I find it unethical for a democracy like Sweden not to maintain a well-functioning defense. Of course, to be useful, a military needs be well equipped. And you see where this is going: whomever have the better propellants fire and fly longer. Developing or producing such materials, then, is not inherently unethical – in fact, it can be quite the opposite.

It is in this light that I was just stunned to find that, as of this posting, my PhD thesis has been downloaded 7185 times. That is not normal for a PhD thesis, and worrying for I suspect that those downloads are not motivated by a great need for environmentally friendly access to space, or non-toxic fuels for satellite navigation, but low-signature propulsion.

Publishing advances in the field of energetic materials in the open literature can, in some cases, raise ethical concerns. At the same time that is true for many fields of study, where outcomes can have multiple uses. For what it is worth, I hope that the share of my scientific work that deals with energetics will prove more inspiring, helpful and interesting, than harmful.

If I ever feel obliged to give up my passion for astrobiology and chemical bonding to pursue energetic materials full time, most of us will have bigger problems than publication ethics to consider. For in such a situation, the work would not be published. It would be ethically applied.

— Martin, July 23, 2025