As a scientist, it is a good feeling to come across something that contradicts textbooks. Better still to contribute to a discovery that could help explain chemistry on a planetary – or should I say moon-etary – scale! This post is about a paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in which Fernando Izquierdo Ruiz, Álvaro Lobato and I teamed up with Morgan Cable, Robert Hodyss, and Tuan Vu at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory to study surprising molecular interactions that may take place on Saturn’s moon Titan. Lots to unpack here.

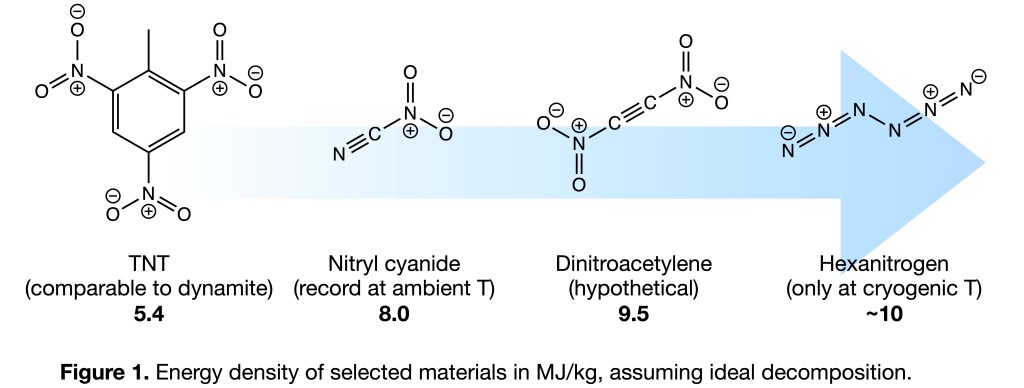

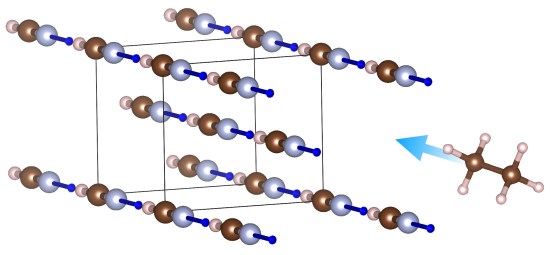

First, any basic chemistry course will tell you that polar and nonpolar compounds do not mix. Yet in this article, we combine data from cryogenic experiments with quantum mechanical calculations to show that hydrogen cyanide, HCN – a molecule more polar than water – can form co-crystals with methane and ethane, two of the most nonpolar substances known. At sufficiently low temperatures, these molecules defy conventional chemistry! They manage this feat because the HCN crystal is differently structured in different directions. In it, all the highly polar (and very toxic) HCN molecules line up in neat hydrogen-bonded chains, reaching from one end of the crystal to the next. Between these (polar) chains are nonpolar cavities, where small nonpolar molecules such as methane and ethane can enter (Figure 1).

So why care? Well, beyond reshaping our understanding of molecular compatibility at low temperatures, this discovery matters because HCN and small hydrocarbons are abundant on Saturn’s moon Titan.

Titan is a special place: it is a moon larger than the planet Mercury, and it is the only other body in the solar system besides Earth that features liquids on its surface, lakes and seas, even rainfall. Two oh-so-slight differences from Earth are that the surface temperature is a frigid 90 K (-180 ℃) and that the seas and lakes are not made of water but predominantly methane and ethane. Titan is also enveloped by a yellow haze of organic (i.e., carbon-based) molecules of unknown composition. The haze is formed through complex atmospheric chemistry that is driven by radiation brought by Saturn’s colossal magnetosphere, as well as the Sun. Foremost among the products formed in the atmosphere is HCN – there are even clouds of it!

HCN, in turn, is super fascinating, as it has been shown to readily react to form many of life’s building blocks, such as nucleobases and amino acids. While toxic to humans, by evolutionary accident, it is likely essential for the formation of life as we know it, and maybe for other kinds as well. All this to say: Titan is a truly alien place on which unintuitive chemistry far from Earth-ambient conditions governs!

Our discovery that some of the most abundant molecules on Titan can mix intimately, on the molecular level, may therefore help explain not just prebiotic chemistry, but also the physical evolution of Titan’s surface. Better yet, we may find out in a few years!

Figure 2 shows Dragonfly, an SUV-sized nuclear-powered autonomous quadcopter, set to launch from Earth in 2028. Yes, this engineering marvel is by any metric very cool. If all goes well, it will make landfall on Titan in 2034, and begin studying its surface chemistry for signs of life.

I hope our work, and its greater context, will inspire more scientists, young and old, to look beyond the familiar world of ambient conditions. There is so much left to uncover about what transpires in more extreme environments, whether at the high pressures created by an impact, at the center of a planet, inside a diamond-anvil cell, in the heat and acidity characteristic of our neighboring planet Venus, or, like on Titan, at cryogenic temperatures.

Some who read this might ask: why work on such ethereal stuff, so far detached from our very real challenges here on Earth? To those I would like to share my philosophy of science: when we learn to understand extremes, our challenges at ambient conditions pale in comparison. Or, as Roald Hoffmann once paraphrased:

“The fringes are more than the frame; they define the center.”

Finally, I will admit to my main reason for writing this post: it is to emphasize just how interdisciplinary and downright awesome chemistry – the central science – can be. Learn it, and you might discover many secrets on this world and beyond.

– Martin, September 28, 2025

P.S. The paper “Hydrogen cyanide and hydrocarbons mix on Titan” is behind a paywall for the first six months. You can find an earlier free preprint here.